The old man had been rushing to get onto an elevated. His eyes had been smarting with the cold. On the icy platform he had squatted down to keep warm and had only closed his eyes for a moment. He must have dozed off. Dreamed he was back at Flynn's saloon, sweeping out. He had opened his eyes, startled by the motorman's bell. The northbound was ready to pull out! The old man was standing on the wrong side of the tracks. Blinding white light glared in his eyes. The tracks shimmered with a frosty glare. He blinked and cocked his head to shift the light. Ice. Icing. Christmas Market. Vaclavsky Namesti. Gingerbread. For a fraction of a second, he forgot what he was doing there. He shoved the image of gingerbread aside and the icy rails became only what they were. Little mirrors of ice that lay on and between the tracks. Need to get across. . . He stepped off the siding.

ALL NATIONS PAY HOMAGE TO SANTA CLAUS SOAP.

SOAP OF THE WORLD'S FAIR.

The words and picture of a barrel-bellied Santa lunged at him from the opposite fence as he began to sprint across the icy rails.

SOLD EVERYWHERE.

MADE BY N.K. FAIRBANK AND COMPANY.

Under his right arm, he had a pasteboard portfolio. Some diazo print sheets of Prague sewer lines that he had drawn. He was a good draftsman, his heart pounded, good draftsman. . .good draftsman. . .his left arm was juggling the sheets when the other train rolled around the corner. The motorman neglected to ring his bell. The train just bore down on him, blossoming like a rose from the corner of Old Man Klima's eye. He spread his arms and legs wide with a burst of energy and sent the papers flying. For a second it seemed that he had cleared the train. But he felt a crushing weight and saw that an axle had pressed down on the bone of his ankle, sheering and crushing. He had almost made it.

The ankle was half crushed and the doctor decided to amputate the foot. The expense of this operation set Klima's family back and took most of their remaining nest egg that they had brought with them from Prague. Being hampered in his ability to get around and to find jobs, Old Man Klima hobbled downstairs to the street and took to feeding the pigeons. Feeding those birds was the high point of his day. The humor of his situation did not escape Mister Klima. It was trains which had brought him to Chicago. He had always loved trains and used to spend hours at the Union Station overpass, just watching them pull in and pull out. One of the reasons he had argued his wife into going to Chicago of all places in America was that it was the train capital. That and the World's Columbian Exposition. Railroads and rubbing shoulders with history. Klima had reasoned out that Chicago was the place to be. He hadn't realized that a man could be in the place to be and still find himself crushed in the scramble. Mister Klima's thoughts avoided trains now. He had found some friends in the pigeons. The combination of an interest in pigeons and an interest in trains was not unique. Doctor Dvorák, it was said, came up with some of his best music while visiting with his brood of doves and pigeons.

No brilliant solutions came to Klima as he watched his friends the pigeons. He also watched his wife and the children scramble to take up his share of the load. He lost weight and became a shadow of himself. Klima's son Anton was working on a good tile setting job and told the old man not to worry. There were still jobs out there for a journeyman tile setter and he was never out of work. Emma, Julka, and Maminka were, at that time, spending from sun up to late in the evening sewing and finishing coats for Mister Field's store.

One day the visiting nurse lady came. Klima hopped over to the door on his crutches and opened it. The woman was dressed in a dark blue serge suit and she had something like a nesting partridge on her hat. He didn't like to see a perfectly good bird stuffed on top of somebody's hat. So, what did she want, this bird stuffer? Klima looked out at her indignantly.

"Is this the Klimova family residence?" asked the nurse. Being referred to as Klimova didn't bother Mister Klima. But it was something about that bird. He didn't like to be called Klimova by a woman wearing such a hat. How could he explain that his wife's last name was different than his? Men and women here had the same last names. Here that was different, too. But now the woman was growing annoyed.

"Well, yes or no? Are you Mister Klimova?" The bird looked at Mister Klima with a sad, glassy eye. Don't admit to a thing, said the look in the bird's eye.

"No," he said. "This is not the Klimova family." And he slammed the door. Gangrene set in. The poison did its work rapidly. Mister Klima drifted in and out of consciousness. He saw himself running over a hill with Anna, his wife. They would sit by a little stream and there was a bird that landed right on her hand. It was. . .It was. . .That damn bird from the visiting nurse's hat. Klima angrily swung his arm at it. He roused briefly and tried to speak to Emma. She was wet with tears and was mouthing prayers. His mouth moved, but oddly there was no sound. They must know what he was saying! But. . .then. . .the clouds rolled in again. He was at the Christmas Market on Vaclavsky Namesti. The old women held up great hearts of gingerbread on scarlet ribbons.

"Perrr-nik! Perrr-nik!!" They cried. The cries faded slowly. Old Man Klima no longer had to worry about the tyranny of separate gender names.

This was the era of the opulent funeral. The Klima family was routinely bilked by their countryman the undertaker. The plain pine box was given a coat of stain and they paid for "mahogany." Anton picked a big floral arrangement that would have done well around the neck of the winner of the Kentucky Derby. It costs the very earth, thought Anton, who was trying to keep such thoughts from his mind as he sat in the front row at his father's wake. The clinking of the shovel was the only other thing Anton could recall about his father's burial. The dirt was so frozen and resisting. Hard as life itself.

That day eighteen-year-old Anton became the main wage earner in the Klima family. Anton had picked up his trade quickly, but he was a little over sure of himself. He had never had to look far for a job in tile setting. Prague was a city covered in lapidary tile work. His teachers had been the best. And since coming to America had he not worked much overtime? Was he not branching out into making casts for terra cotta ornaments, as well? Such skills as these could never go begging. Anton did not walk like the tenement garment workers. He was skilled. He held his head high and didn't hunch his shoulders. A shame, that garment trade. The sooner his sister and mother were out of it, the better. But Anton had no fears. Tile was going in everywhere. Or so it seemed.

But the slump came suddenly in March. Anton had a strange feeling, like sand being let out of a bag on which he was sitting. His jobs ran out from under him. Anton, only two years in Chicago, was one of the first to be fired from his gang. That was in early May. Then he couldn't get hired onto any other job, even with his local references. He took to visiting the buildings around Chicago where he had worked as a tile setter. This was the time in our history when skilled labor came cheap and they tiled floors, walls, ceilings. . .everything. The Auditorium Building by Adler and Sullivan had just gone up. Sullivan took an interest in ornament and he encouraged the use of tile and cast metal. Even in his large stores, such as the new Carson, Pirie, Scott and Company Building. Office blocks encrusted with tile work sprouted overnight: a gemlike showplace of the tile setter's art, Krause's candy store, a dozen churches, banks, theaters.

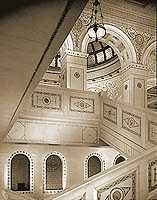

Anton started back for home. He could see the tall Loop buildings up ahead as he walked south. He headed along Michigan Avenue toward the library. Before the Panic had set in, Anton had been setting tile on the staircase of the new Chicago Public Library. The whole thing was still a couple years from completion. Nothing in Prague surpassed this staircase, as far as Anton could see. The white Carrara marble gleamed around the little bits of mother-of-pearl, semi-precious stones and prepared mosaics of glass. Tiffany sent the glass mosaics in a piece and Anton just popped them into their assigned slots. He enjoyed the other parts more, where he actually had to set the tiles and stones.

He walked into the entrance to the library. A few of the men waved or seemed in some way glad to see Anton. But they were also embarrassed by Anton's standing there watching them work. A tile setter named Francesco grabbed Anton's muscular arm and said to him that he should go hire himself out as a bouncer. He hadn't given the suggestion much thought at the time. He had looked up at that great dome and had knitted his bushy eyebrows. He felt more peaceful looking up at the great blue skylight. Anton had his worries, but he never knew the blues he couldn't shake by going and looking at the grand stairway of the Library. The old man had been a great reader and was always telling the children stories from Homer, Shakespeare or-a favorite of his-Jules Verne. Mainly, the old man had read these stories in Prague in cheap paper editions, but he remembered the best stories in his mind. The names in alternating azure and gold that ringed the dome of the library reminded Anton of the old man. Plato, Emerson, Shakespeare. . .Anton had been an impatient boy. He had longed to play ball and other games with the street children instead of reading. Now he wished he had done more of that. The old man could call up whole scenes and dramas from his mind. Even when the hard times hit him, sometimes he would put a hand on Anton's shoulder and think of a funny passage from a favorite book of his. . .or from Mister Dooley, the column in the newspaper. Anton watched. The tile setter was putting the end on the letter 'm' in Emerson. Other letters were green malachite or azure tile surrounded by mother-of-pearl. He felt lighter than air as he looked up beyond the names at the blue glass Tiffany dome. Motes of dust danced before Anton's eyes in the blue light. They looked like tiny beings. He puffed his cheeks and blew. The little dust dancers whirled around. Anton felt that he was one of those tiny blue motes being buffeted here and there. He puffed out his cheeks and blew scores of little Antons into a whirlwind of activity. A few tiles fell off a scaffolding, clattering onto the marble steps.

Anton started back down the stairway. Except for tiny scraping noises when the men mixed their grout on the scaffoldings or dropped a couple tiles, the library stairwell was silent. Today, no marble pavers were being moved up the stairs. They were just finishing up the trim on the second floor railings and some of the quotations around the base of the skylight. Blue light covered Anton as he walked down the stairs. He walked out of the cool shadows of the library and into the sunlight of Wabash Street. On a construction fence was a sign for a meeting at Central Music Hall regarding unemployment in Chicago. William T. Stead was listed as principal speaker, but representatives of the cloakmakers' unions were to speak, as well.

Anton ambled in the direction of central Music Hall where the meeting was to start in about one hour. Before this, nobody would have caught Anton Klima at one of those union meetings. For one thing, they seemed to be dominated by a lot of intellectual Germans. Such men as August Spies and Louis Lingg. After a lot of those fellows had been rounded up for their involvement in the Haymarket incident, the meetings withered like violets in the hot sun. There were lots of raids. Anton knew where trying to better one's lot could have gotten him under the Austrian emperor. Into an Austrian prison. Why should it be any different here in America? One soon lost one's hopelessly ideal views about America and learned how to get by. By temperament Anton was not a joiner. He reasoned that if he kept to himself, then he would be responsible only for his own mistakes. If he joined anything, he could be held responsible for the mistakes or even crimes of other men. But now with his father dead and himself out of work, he decided to see what the meeting was.

He pulled at his hair, trying to brush it down. To look respectable. Maybe someone there would know of jobs. . .Anton stopped at the entrance of the Central Music Hall, State and Randolph. He watched as elegant carriages pulled up, depositing finely dressed matrons. People piled off the street railways dressed in everything from finery to ragged flapping jackets. So diverse a crowd should hold no danger of being broken up by the police as a secret meeting. Anton admired the marble facings as he went into the great stone arched entrance of Central Music Hall. He slipped up the stairway to the balcony and found a seat toward the rear of the auditorium. He kept one eye on the exit nearby in case of a police raid as the assorted speakers and dignitaries began to fill the stage. People in the audience muffled their talk and shuffling as Mister Stead himself mounted the platform. Anton assumed that this wiry fellow with the red hair and beard was Mister Stead, since he was greeted with a loud burst of applause.

Stead called for everyone's kind indulgence so that he might identify the many notables present. He went down the row of people on the stage: madams, preachers, businessmen, labor leaders, society matrons, police officials. Anton jumped when Stead's voice rang out, as he gestured to a man on his right, naming him as one of the Haymarket defendants just released by Governor Altgeld. If there hadn't been an Assistant Chief of the Chicago police up on the stage next to the Haymarket fellow, Anton would have bolted and fled from the hall. He ran his hand through his hair nervously and looked around. No one else seemed nervous or scared to be there. Anton gave a little shrug, crossed his arms and settled down into his chair to see what would happen. The Hull House motto was prominently displayed across the back of the stage on a long white sheet. WITH, NOT FOR. That said it all, apparently. Under the gleaming banner, Stead rose to address his audience. He thanked all the trade unions for sponsoring his talk and listed a few of these by name. Some of the more radical and agnostic shuffled in their chairs as Stead opened with a question, "What would Christ think of the city of Chicago, its fine Columbian Exposition coexisting with a growing depression? If He came to Chicago today, my friends, what would He think of that? The police could do more than to protect the vice in the red light district," said Stead. At this, there was some hissing mixed with applause. Stead waited.

"No, it is not fair to take away the only means of sustenance for some in the name of reform. This is true. And it is a curious form of reform, indeed, when well-heeled ladies come into the slums and say to change this or that about oneself while offering no means of support to take its place! Scattered applause greeted this last. This is why there are several people here who represent the working men's desire to make better wages, wages upon which one may truly support a family. Rather than hearing me speak upon a subject in which I am, at best, but half informed, let us hear from one of your Chicago labor leaders-Mister Thomas J. Morgan!" Stead turned and applauded as Tommy Morgan came to the podium.

Morgan, a stocky, little Welshman with a upturned nose, waved his hands for silence. Morgan turned to Mister Stead and said, "I wish to thank the most illustrious journalist England has produced in this century! Your interest in our troubles here in Chicago, Sir, is nothing more than miraculous!"

Morgan thanked all the workers for turning out, as well, but it was not they he really wanted to address. "No, my friends, I am addressing the upper classes this evening." He turned sideways and nodded at a couple of socialites on stage. "It is good to see our Gold Coast here in force this evening, said Morgan, because there is a story you have, no doubt, not heard. In early June, many of our families tried to have a march to the Lake Front where we would assemble peaceably to beg for work. Do you know what happened? The police were ordered out in force to push and club our people out of sight. That is, ladies and gentlemen, the tourists were not to see our people-our very own Chicago people! We were driven back along the streets to the tenements so that no visitor to the World's Fair would have to see our misery. What would you do if all your avenues for redress were so closed off? Would you sit quietly by and watch your child sicken?"

Morgan searched the faces of the Society people, who were seated in the first couple of rows. "I do not have all the answers to unemployment here. Mister Stead has at least made a start with his street-cleaning brigades. Those should be running by noon tomorrow. And we are going to operate them in the neighborhoods with the most uncollected refuse. Miss Jane Addams from Hull House, who unfortunately could not be here tonight, is going to oversee our work there in Packingtown herself!" A burst of applause greeted the name Jane Addams. Morgan wiped at his eyes and waved a hand for silence. "That's all I have to say to you now. I am too overcome to go on, but I thank Mister Stead for this opportunity! And remember, without justice for the poor, they will turn on this city! They will have to revolt!" With this, Tommy Morgan returned to his seat.

Shouts of indignation had gone up during Tommy Morgan's speech. Anton saw the Police official at the door grip his baton and look up to the wings of the balcony. There probably were plain clothes detectives in the crowd. Anton scanned the exit to see if it were clear. It was. He would be out and down the stairs in a flash if anything broke loose. Stead made a bridge to the next speaker. "Ladies and gentlemen, it is true! Justice and mercy will never go out of style to Christ," he said. "Hope must be given to these victims of squalid industrial growth or they will revolt! We are pleased to have with us delegations from the Cloakmakers' Union and the Ladies' Cloakmakers'. . ." Whatever was said after this Anton did not hear, because he had run out and on down the street. Not only words about revolt from Tommy Morgan, but from Mister Stead. Anton thought the crowd might get unruly, so he had to cut his risk there. "Never volunteer" was the Klima family motto. Theirs were the neolithic ancestors who had stayed in the cave after dark and hence were never eaten by the sabre-toothed tigers. But Anton hated himself sometimes. Other people were willing to be clubbed in the head for their beliefs! Anton didn't like to think he was callous. He did grieve when his friends were clubbed by police at some demonstration or other. He despised the people who would go and take jobs when others were trying to hold out for a living wage. Anton never took those jobs. There were just other things in life besides politics and workers' rights. The ones who were all full of these things talked of nothing else. As though the rest of the world were a closed book to them.

Anton walked at a good clip away from the Central Music Hall, casting a nervous glance over his shoulder every now and then. No one there. Anton could feel life with his eyes, he argued to himself. He had a feeling for the colors and textures of the bits of lapis that he patted into place on his last job. He loved the cool feel and the vivid color of the malachite chips he had placed around the fireplace of that hotel on Wentworth. But Anton's labor friends didn't pay attention to trifles. They didn't care a bit how the light shone at a certain time of day and made reflections from the glass in the leaded windows into little boats of light that sailed up and down the walls. Anton had never actually talked to anybody about the little lights and the way he enjoyed the colors in the tesserae that he set into complex pictures. He only knew that this took up a portion of his mind which, if he were a truly committed fellow, would be given to thoughts of the struggle.

Now Anton was well down the street, four blocks from the hall. He slackened his pace and stuck his hands in his pockets. Whistling, he looked down and noticed a tiny hole in his pants from the day his friend Charlie had taken him to see the big cauldrons where they poured the blazing metal into iron and steel bars. That had been magnificent! The colors ranged from yellow as bright as the center of the sun to blazing reds, occasional flecks of green lights or purple lights where an impurity in the bar came to the surface and was burned up. The heat. The noise. They pressed into one's skin and made the breathing hard. Still, what colors! Anton felt like he was looking into the heart of the sun. He couldn't believe the color of that light and stood rooted to the spot. But Anton's friend pulled him by the arm.

"C'mon, artiste!" Charlie had yelled over the din of the inferno. He pulled him over to an old Welshman was using some of his breaks to make sketches of the open hearth. The man's name had been Jenkins. Anton saw the small water colors that this fellow kept in his locker. If he had only had the money, Anton would have bought one of Jenkin's paintings because that old fellow captured the spirit of the molten light. Watercolor was usually muddy and faded out, but not the way this old man had used his paints. Anton had been sorry when Charlie made him go on and see the other parts of the mill. He had wanted to stay and ask the old man who had taught him to paint that way. Too bad he hadn't gotten the man's address because that old man was turned out of the mill when the plant shut down at the end of the season. Anton's friend didn't know where the old man had gone. He was just gone and now Anton would never discover where he learned to paint so amazingly.

Anton nudged a rock with his hob-nailed boot, it was a curiously regular geometric shape. When Anton got another job, he meant to gather up many of these things in a wheelbarrow and begin to build a chest set in with shards of bottles, pebbles and funny bits of metal. Later, Anton meant to build a cottage. He could do it, he could save some pennies from each pay toward a piece of land. Anton's toe turned up a bright red pebble. He put it into his pocket. Could a house grow from this? In the old country they believed all kinds of things. If Anton's Teta Hana were here she would probably say to put that rock in a tub of water, say the right words over it and-poof-a house would grow there. On second thought she wasn't all that stupid. Stories like this were what Teta Hana used to say when she wanted Anton to open his mouth. He would listen to her, gaping like a cod, and she would dump some foul-tasting oil down his throat. It always worked, too.

Anton was growing more disgusted with himself when he got back to the tenement and watched his mother and sisters sewing at the usual coats. He hung his vest on a peg and walked over to the little cooking gas jet. Smells of cabbage. Anton lifted the lid. No meat. He placed the blue lid back on the pot. A trapezoid of sun hung on the wall in front of Anton's face. The quizzical shape seemed to be asking to be interpreted. Make sense of this, said the shape to Anton. He knew that he was doing it again. He had no right to think about shapes the afternoon sun made. Wasn't his stomach empty as it was every day? Empty. Yet here was Anton, the man of the household, looking at shadows and lights on the walls! He turned his eyes sidewards at his mother, who was bent over her cloak, stitching and straining her eyes after the last rays of the day's free light. Anton made a wry mouth. Shrugged. In the morning he would go out again. If he couldn't work as a tile setter, he would work at anything. What had that fellow said? Bouncer. Why not? Anton was big enough. He would go be a bouncer.

Go to the Top of this Page

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Table of Contents

Waking the Dead

Copyright © 1997 Gloria McMillan and Fly

Neleth Press. All rights reserved.