"Funny chap," Stead mumbled to himself as the hansom jolted along the rutted South Chicago street. "No, that detective Wooldridge is not at all in his right mind, I should guess. His police methods would never do back home. But that does not appear a handicap in Chicago. . .no. Interesting place. . ."

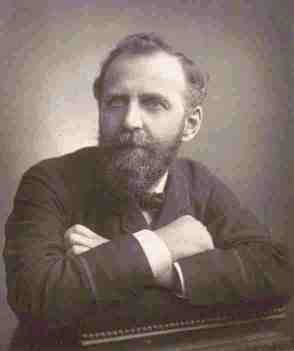

Stead tapped his cheek with his pencil as he talked to himself aloud and made notes for his book. It was now sometime around midnight and the only light in the back of the cab was the reflection of the driver's lantern. Stead could barely see to make his notes. Then he had to stop writing as his hansom took a deep pothole in the road and spattered mud onto the cab's windows. The rain outside had lost its force, but hovered above the ground in a mist. Stead had to keep wiping at the window as his breath continually fogged the pane. Little condensation drops made rivulets down the window. Stead wiped the fog from the window with a pocket handkerchief. As he wiped the glass yet one more time, the cab was passing a lantern and caused Stead to start at the look in his own eyes. Stead's wide, russet beard shaded his regular features and full mouth. These features contrasted sharply with his eyes. But live with them as he must, Stead had never gotten used to his eyes' intense stare. In the lantern light, Stead could see his eyes dart about like a nocturnal bird's, missing nothing. His face fell back into darkness once more as the lantern light faded, but he continued scanning the gloomy tenements. He did not know how to relax and take time off his endless vigil.

As he rode along and recorded the details of the strange Chicago streets, the face of the flushed girl accusing Field at the reception returned to Stead. She had a sweet little mouth and a dimpled cheek. Couldn't have been more than her early twenties. Perhaps more than Stead's journalistic instincts had become aroused, but Stead never acted on impulses. He sublimated everything to the goal of helping the poor. What appealed to Stead the most was the way that girl had looked Field squarely in the eye and told him her piece. . .for all the good that was going to do her. Wildly intemperate, these Americans. Stead was wildly intemperate himself. Perhaps he should emigrate. . .No, no, he was far too fond of tweaking the beards at home.

Getting back to cases, Stead turned over the questions asked by journalists everywhere. Who? What? When? Where? And a did she do it? And how should he interview her? Stead had a lot of catching up to do. He did not know these Americans the way he did people at home. But. . .first things first. Stead paused and picked one of his teeth with his pencil and spit out a bit of ham. Had been bothering him all night, that. Getting back to the reason for the little excursion, Stead thought he might do well to establish this woman's connection with the reformers at Hull House. But wasn't she a bit extreme, even by Chicago standards? What could be this young woman's motivation for such a savage attack upon Mister Field? Not that he himself was above making such savage attacks on the rich. Coming from a young woman, though, Stead had to admit such behavior bordered upon the vulgar. What had she hoped to gain by it? Stead tapped his pencil against his cheek.

He peered out the window. Refuse sailed along the gullies in the obscure street like little boats. The cab had to dodge among crates which had floated out toward the center of the road. A rat rode one of these crates, scurrying from one corner to another as the crate bobbed down the sodden lane. Stead made a mental note to use this image as a comparison to the behavior of the aldermen at City Hall in the final version of his book. The rat was now having a tough time negotiating some rapids caused by a dip in the road. These streets had no uniform grade, but houses seemed to bump up against each other at various heights and angles. His ride from downtown to Harrison Street Station showed Stead why people said that driving to the grounds of the World's Columbian Exposition was like running the barricades of Paris in eighteen forty-eight. Streets changed grades every few houses in the most bizarre fashion. A house would need stairs up to the front door. A few doors down, the front door would be a semi-basement. Pure bedlam, thought Stead, yet the town was not unappealing in its potential for change. Chicago was a very striking place and so were its people.

Stead recalled his conversation with the madman-detective at the party. A bit of the March Hare seemed to cling to the man's side whiskers. The self-proclaimed World's Greatest Detective had told Stead that Chicago's streets or lack of them were lining many aldermen's pockets. Detective Wooldridge told of these feats of fiscal mayhem as if he were describing a wonder of nature, like Niagara Falls. Such was Wooldridge's respect for boodle. The Americans used this term boodle when they meant graft. Wooldridge thought Chicago had invented graft like so many other modern marvels, for instance, the Pullman palace car. But no such luck. They had a century's-old tradition of graft in London. Or maybe, one might say, many little grafts. Possibly nothing on the grand scale of these Chicago parvenus, but precedents for this boodle went farther back in England. Stead had felt a surge of pride when he had defended the ancient graft-taking of his native isle to Mister Wooldridge.

"Very well, sir, they may have had boodle longer, but do they ride thieves piggyback to the station house in London?" Wooldridge had asked then, beaming smugly. Stead had to admit he had never heard of such behavior. The World's Greatest Detective had puffed out his gauche, pin-striped vest and announced that he often rode thieves to the station house and that not a one had escaped. Even now Stead smiled at the image of the wiry detective rounding up the unruly like a cowpoke out on the trail. But then Wooldridge had spoiled the moment by going on to ask Stead the dreary, usual questions about England and the Queen's health, questions which were as frequent as they were boring to answer. Just to turn the tables a bit, Stead had asked this puffed up specimen of a mad American how he pictured England. Wooldridge apparently pictured England as a sort of Pickwick's club. Grass is always greener somewhere else, eh? Stead had chuckled and patted Wooldridge on his shoulder. Tears of laughter had risen into Stead's eyes. He felt it only fair to balance the image. "My dear Wooldridge, English mothers abandon or sell their girl children into prostitution. For rum. Not so different, is it? Just the same, in point of fact, as in Chicago. Only here, I trust you will agree, the price tends to be beer or Irish whisky."

Wooldridge sensed that Chicago's unique grandeur was being threatened. He countered, "Chicago's got the most vicious criminals in the world. I know, since I haul them in!"

Stead pressed his case that Chicago had very little on jolly old Europe. "Your toughs who rob the drunken guests of the panel houses like Maude Allen's are merely the brothers of some of the same in Whitechapel," he said, staring Wooldridge boldly in the eye. "Neither unique, nor unheard of." Stead had been pleased to see that this news brought Wooldridge's eyes out in a sort of bulge. Clearly the man had been straining for something that would justify the title he often gave to Chicago: Sin Capitol of the World. A light went on in Wooldridge's eyes. He said in a voice that dared Stead to oppose him, that Chicago had one prize even London could not claim. A saloon that averaged about twelve thefts per night. Its owner, a truculent Irishman by the name of Mickey Finn, was rumored to be putting drugs into the customers' beer and then cleaning them out. Detective Wooldridge had said that he was keeping a special eye upon Mister Finn at the moment. Stead envisioned the agile Mister Wooldridge riding the vicious saloonkeeper into the station house.

Quite an entertainment for the neighbors, thought Stead. "I'll bet you haven't one of those!" Wooldridge had crowed.

"Another one who is one of the worst. . the very worst. . ." Wooldridge stopped, perplexed. Stead asked him to continue.

"Bohemian, he is. A soothsayer. He's got whole families under his spell. People's dying and he's collecting all their insurance. Poison," said Wooldridge. "He's got to be poisoning them." Stead ventured that Finn and the immigrant magician sounded like two of a kind. Wooldridge said to take a word from the wise. Of the two, he would take his chances with Finn, rather than Bizek, the magician-poisoner.

"Scum of the entire planet," Mister Stead, lamented Wooldridge. "The scum always comes to the nineteenth precinct. And I'll wager you can't top that in London!" At this, Wooldridge hauled out a pocket handkerchief and snorted. Stead decided not to compete. But instead of killing the debate, this proved a green light to Wooldridge, who apparently had other secrets to share on the subject of human nature and sin. One of the first things that a foreign visitor like Stead should be aware of was the moral depravity of the blacks and the immigrants. Fathers raped daughters, sold their wives to their bosses for an extra few dollars a week, the World's Greatest had said and winked. And children, he said, nudging Stead in the ribs. Yes, children left unattended in tenement apartments fell out of windows and were smashed like eggs down in rubble-filled alleys. Girls were grabbed on their way to work, drugged, and set up in brothels. Detective Wooldridge had listed these horrors with a smile. He had rescued dozens of such girls from brothels. A point of pride. Wooldridge beamed.

"What becomes of them, then?" asked Stead. Wooldridge had not given much thought to the question, momentary drama being his forte. Stead could guess. A girl could go back to a crippling machine from six in the morning until seven at night. Her legs soon would give out. Back at the old trade in a week or a month. Even the store clerks sometimes became prostitutes, Wooldridge announced, suddenly shocked at the pandemic of sin.

Store clerks, indeed. Stead knew a bit on that score and he told Wooldridge so. He had questioned the managers of Field's and other department stores for his book on Chicago. Almost to a man they denied that any girl would ever be driven to prostitution from economic need. One manager had sneered that only girls who found it necessary to purchase scents and other finery would feel enough of a pinch to become prostitutes. Any girl should be able to exist on four dollars a week. The managers had been affronted by Stead's questions. Then Stead had talked to some ribbon clerks from Mister Field's store. They said that Field's bouncers always made it a point to escort any organizers for the Knights of Labor right back out the door, practically before they got their noses in. But the pimps? Oh, Field let them breeze right inside. They were never stopped or bothered in any way and so could approach the girls any time they chose. Stead could see that all this meant steady employment for Mister Wooldridge. Wooldridge would continue to rescue the girls and the girls would continue to go back to prostitution. Like a snake eating its own tail. There was no end.

The rain fell and misted the window of the cab. Many things were the same in Chicago and in London, not merely this weather. But that, too. In both cities a downpour caused the poor to mold themselves into cracks, crevices, culverts—anything—just to be a little less damp. The rain had stopped. Still, no one was out.

The hansom drew up to the front entrance of Harrison Street Station. Stead climbed down and paid the cabby. He looked at the shadowed facade of the station. And there they were. Huddled and slouching. The floating army of homeless men. A canvas awning of a closed shop across from the station formed the village green for the tramps. Soon they would be let into the police station for the night. They would line the corridors on louse-covered newspapers. They killed the minutes and picked their fleas, meanwhile. One man was tossing twigs into a small fire in a trash barrel. A couple more were trying to dry their rags and shoes. They pressed around a lanky youngster. Stead had talked to him just the day before and knew that his name was Prendergast, but they called him Prendy. In the flickering light of one candle, he was reading aloud some headlines from the paper. Prendy hawked papers over on Lasalle Street. He had told Stead that his life at home was a bore. He spent half of every day helping his mother. But among the boys here he was somebody big. He read well. His voice soared with the stream of the dramatic events of the day.

"Let's see. . ." Prendy announced. Stead watched as the young town crier rattled the pages impressively. "Listen, boys!" "The City Council Will Take Up the issue of Garbage Collecting Once Again. . ." This brought laughter and a few jokes about the difficulty that Sanitation would have distinguishing the Council from the refuse. "Here's one for you! Mister Yerkes Quoted in an Exclusive Interview, no less." Prendy looked over the top of the paper at the boys. A knowing look. See page five, he said, and rustled the sheets. Stead moved up, right behind the circle of men who were listening to the young man read.

"Yeah, here, here's what Yerkes said. The straphangers pay the dividends to my stockholders. Let the cars hold three times as many as they were designed for. Let children and old people fall off. Let the motormen be unable to see for the crowds. Nobody can make Yerkes do a thing! My company creates employment, so the public should be grateful and. . .One of the tramps interrupted Prendy's reading." Said he knew that about Yerkes all along. Hadn't they just been burning effigies of him over in Bug House Square? Prendy said, as if to defend him, that Mister Yerkes had bought a paper from him on State Street and had tipped him a dollar.

The others groaned and nudged each other. "All the time, you're saying things like that. You must've been dreaming, Prendy," said a dirty blonde fellow with a gimpy leg.

Stead walked into the midst of the homeless men. He asked whether they had seen a dandy sort of gent leading a girl into the station. The girl was dressed as a waitress in a starched black pinafore. One of the boys allowed as he had seen such a thing. Prendy looked annoyed at the interruption of his act. Stead walked off toward the station house and Prendergast resumed reading to the boys. His voice trailed behind Stead as he walked. "Listen up, boys. It says here, New Cholera Cases. . .There's eight of them in Hamburg. . .Eleven in Budapest. . .And can you feature this? They arrested a Gang Engaged in Kidnapping Girls in Austrian Galicia for Turkish Harems!"

Stead walked through the limestone arches of the police station. At the far end of the vestibule, two gas jets burned, sending flickering blue and red shadows up the wall. Beneath the jets sat rheumy-eyed Callahan, the desk sergeant. He had been on duty when Stead was accompanying prostitutes to the station the last month. The two men exchanged nods. Stead asked Callahan what he thought of the weather. Callahan said in a tired voice that rain was a fine thing, indeed, for the ones indoors.

Stead leaned an elbow on Callahan's high desk and gave him a meaningful look. "What about the mayor's plan to reform the police, Callahan?"

Callahan loved intrigue. He blinked, a flicker of interest coming into his eyes. He leaned far up on his elbows and his head almost touched Stead's as he hoarsely whispered, "Would you be meaning that so-called divorcing of the force from politics?" Stead nodded. "The firing of Republicans may have the effect of separating the two," said Callahan in hushed tones. Stead asked how that could be the case. "It's that simple," said Callahan. He enumerated on his fingers. "The Democrats believe that the police can be divorced from politics and the Republicans do not. So, you fires them as ain't believers to give the thing a chance to work." A smile spread across Callahan's genial face. While Callahan seemed to be feeling cheery, Stead asked if Detective Wooldridge had brought in a young woman earlier in the evening. Callahan nodded and said that the woman's name was Alzina Stevens. Then he pointed his nose over at a bench down the hall where a woman in a white blouse and a black pinafore was sitting slumped dejectedly among a rowdy chorus of whores.

That will be a lesson to her, thought Stead. He had heard the young woman's remarks to Mister Field about the condition of prostitutes in Chicago. She had probably never seen one in her life. That was usually the way it was with these reform women. Stead rubbed his hands together and blew into them. This semi-basement vestibule was as dank as a root cellar. One of the girls was offering a cigarette to the girl in the pinafore as Stead approached. He interrupted the transaction to introduce himself.

"Why, it's Mister Stead!" Yvette, a French girl from Mary Hastings's, recognized Stead before he could say two words to the girl in the pinafore. Yvette began pouring her heart out about all the swinishness of the Chicago police, how they had even found her little flask of medicine and taken it from her. The girl was speaking in a torrent. Stead didn't try to interrupt Yvette, but knew she would run down in a minute.

"Where's Maggie?" he asked. Maggie was the little sad-eyed girl who was going to get a whole chapter in Stead's book.

"Lucky for her," Yvette sighed, "it was the night she gets off." No, Yvette didn't know what Maggie did on those rare occasions.

Stead asked to speak to the girl in the pinafore. Yvette replied huffily to go right ahead. She started cat-calling across to some women squatting on the floor on the other side of the hallway. Stead crouched in front of Alzina and introduced himself. She wouldn't look up or speak.

"Miss, I was there at the Palmer reception. I would like to know why. Why did you do it?" Stead started to explain more about who he was, but Alzina interrupted. She knew who he was, of course. She had attended one of his meetings at Central Music Hall, but she was too tired to think, she said.

"And I'll tell you something, Mister Stead, I don't feel very trusting at the moment. Do you know that sometimes they take liberties when they were searching an incoming arrestee's person?" Stead nodded and said that abuses should be reported. Alzina stared ahead in a mindless sort of way. The she looked up sharply, "Not major liberties, mind you, but annoying ones!"

"Well, we need to get you out of here, then." Stead said that he had telephoned over to Hull House and. . .Alzina stopped him.

"You didn't! I wanted to handle this myself. Miss Addams doesn't need to know I. . .I. . ."

"Made a complete ass of yourself?" Stead volunteered with a cheery smile. Alzina just scowled. "Miss Addams didn't sound too upset over the telephone and she will be over to bail you out as soon as she can. Probably late this evening. This was a foolish trick, Miss Stevens."

Alzina broke in. "How long do you think I sat in that waiting room and Field had refused to see me!" She pulled out three little white tags. She had only wanted to tell Field about the tags. She had only wanted Field to put sanitation tags on all his garments. All she was proposing was an inspector who would go around independently of the store management and award the tags. Customers could know that they were purchasing clothing that was not produced under sweated conditions. Alzina finally looked Stead in the eye with a defiant glare. "Mister Stead, do you know that garments have been and are being sewn in rooms where children have died of small pox?"

Stead glared just as defiantly back. "Yes, blast it, I know that. And I have known that since you were out playing tea party with your dolls!" Alzina realized that he thought that she had come from a sheltered upbringing. She whipped off her glove and Stead, following the rapid movement, winced as he saw the missing little finger of her left hand.

Alzina tried to keep her voice calm. "Playing with dolls? Hardly. After both my parents died, I was put to work at a textile mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Twelve years old at the time. The boss said that this accident happened due to my carelessness. He fired me. There was a doctor in town who felt sorry when he saw my hand and he sewed up the stump." Alzina explained that she had clerked in a dry goods store and since then, had been two years in Chicago. She had learned to typeset and had become involved in the typesetters' union. One of her fellow women typesetters had suggested to Alzina that she find a place at Hull House and try to be an angel for the underorganized: women in home industry, foreign born and black women.

"And how is that work progressing?" Stead asked pointedly. "They don't trust anybody," Alzina admitted. "So we are gaining very few recruits. There was one family who seemed interested. . .Oh, it's awful! I got them into a mess," Alzina said, looking down at her finger stump.

Stead was recovering from the shock of Alzina's background. Being used to being the only one making shocking revelations, Stead took a minute to adjust his image of Miss Stevens. He smiled at Alzina and said that there was plenty of work in the area she was describing. Alzina was worried about the two Klimova women, the ones who had been more open to her visitations and who now were in trouble. Here she had promised them that she would square things with Mister Field. "They may be charged for the garments I had burned and. . ."

"May be charged?" Stead told Miss Stevens that she could rest assured that they would be charged. As soon as she could get over to the tenement, Stead suggested that she go and see what could be done to keep the Klimovas from being prosecuted.

"Your friend Jane Addams might guarantee their debt," suggested Stead. Pulling her glove back on, Alzina said shakily that she never meant to do any harm.

"How could Mister Field pursue this when those capes and coats were surely infected with small pox?"

Stead asked Miss Stevens if she had thought to get proof of the infection.

"Short of giving small pox to somebody, that would be difficult to do!" Alzina protested.

"Therefore, before the law, all that has happened is that you have cost Mister Field a number of garments," Stead said, to outline what, to him, was obvious.

Alzina sat quietly for a moment. "A way will be found," she said in a low, controlled voice. "Those women must be protected."

"Agreed," said Stead. "Field is not the most unscrupulous of employers, but he will think now that right is entirely on his side. It is not enough to mean well, Miss Stevens. Things get set in motion. Lives are affected, don't you see?" Alzina nodded. "We need a weighty friend in this work. There is one woman who could bring some real power into our movement. Now, Bertha Palmer. . ." Stead began.

"Bertha Palmer?" Alzina interrupted. "Now I know you are mad. Didn't you visit her palace? She is the wealthiest woman in Chicago."

Stead put out his hand to silence Alzina's objections. He knew all that. In England a countess was one of his biggest backers. "You must come with me tomorrow when I approach this Chicago countess of yours."

"Mister Stead," Alzina said in a syrupy voice, "you may rest assured that I wouldn't miss it for the world."

Go to the Top of this

Page

Previous

Chapter

Next

Chapter

Table

of Contents

Waking the Dead

Copyright © 1996 Gloria McMillan and Fly Neleth Press. All rights

reserved.